The Devil is in the Details: Key Differences in U.S. Data Privacy Laws

The regulatory landscape surrounding data privacy is changing rapidly, with individual states adopting new legislation to address constituents’ privacy concerns in the absence of an overarching federal law.

So far, five states have enacted comprehensive privacy laws: California, Colorado, Connecticut, Utah, and Virginia. The California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) has been in effect since 2020. The California Privacy Rights Act (CPRA), which amends and expands the CCPA, Colorado Privacy Act (CPA), Connecticut Data Privacy Act (CTDPA), Utah Consumer Privacy Act (UCPA), and Virginia Consumer Data Protection Act (VCDPA) will all take effect in 2023. While all these privacy laws impose requirements on covered businesses regarding the collection and use of consumers’ personal information, the laws are distinct, and understanding their nuances is crucial to ensure compliance across state lines.

Common Themes

There are many similarities among these new privacy laws. For example, covered businesses in all five states will be required to:

- Be transparent and provide notice to consumers;

- Limit their processing of personal information;

- Refrain from discriminating against consumers who exercise their rights; and

- Perform data protection assessments.

Further, consumers in all five states will have rights of:

- Access;

- Rectification;

- Deletion;

- Portability; and

- Opting out of certain transactions.

Little Details Make a Big Difference

Despite their commonalities, significant differences will exist between the five States’ laws when they each become fully effective. These include, but are not limited to, differences in:

- Key definitions;

- Scope;

- Exemptions; and

- Administration and enforcement.

When viewed more in-depth, all five laws broadly define the term “personal information” or “personal data.” Unlike the CCPA, however, the CPA, VCDPA, UCPA, and CTDPA borrow terms and definitions from the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), such as “controller” and “processor” when referring to covered entities and their service providers, respectively, and “personal data.” In addition, the CPA, VCDPA, and CTDPA require covered entities to conduct data security assessments for data processing activities that present a “heightened” risk of harm, such as profiling, selling personal data, processing sensitive personal data, and engaging in targeted advertising.

Unlike the CCPA, which allows a private right of action for breaches of personal information, neither the CPA, VCDPA, UCPA, or CTDPA includes a private right of action for any type of violation. The CPRA extends the CCPA private right of action to data breaches that compromise a username and password and creates a new regulatory and enforcement body, the California Privacy Protection Agency. In contrast, the VCDPA grants enforcement authority solely to the Attorney General. The UCPA provides for a bifurcated enforcement scheme. First, the Utah Department of Commerce Division will investigate companies based on consumer complaints, and it then sends cases it deems legitimate to the Attorney General’s office. Then, before initiating enforcement action, the Attorney General must first provide the business with (1) written notice 30 days before and (2) an opportunity to cure within 30 days of receipt of the notice.

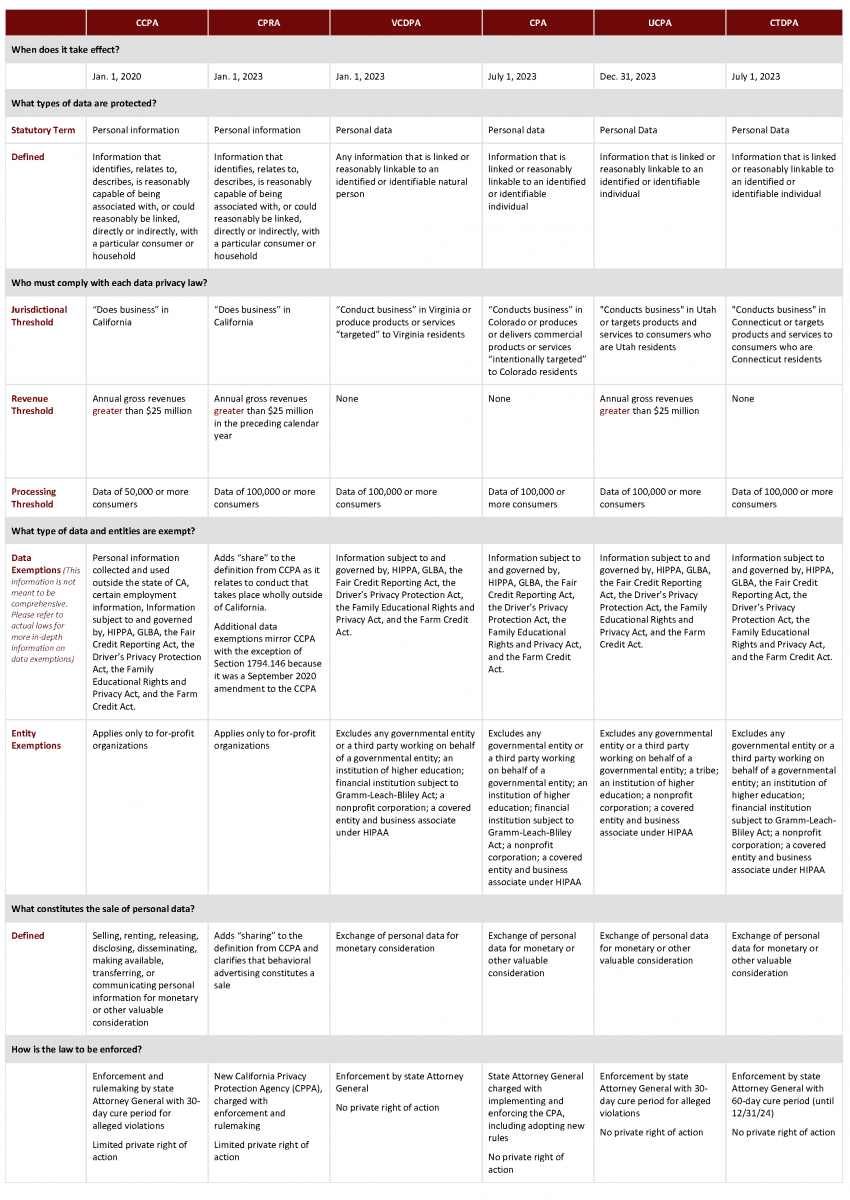

The chart below provides a high-level comparison of some of the key features of each state law:

Preparation will be the key to avoiding issues with compliance and claims of alleged violations. Organizations must review each law in detail to assess the proper application and compliance required. Also, states like California and Colorado have only begun the rulemaking process under their respective statutes, meaning that new or different substantive obligations may yet be forthcoming. Redgrave, LLP will continue to monitor the changing landscape of U.S. data privacy legislation and are available to consult and assist in the development and deployment of successful information governance and privacy policies and practices.

For additional information on this topic, please contact Martin Tully at mtully@redgravellp.com.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and not necessarily those of Redgrave LLP or its clients.

By M. Lynne Hewitt and Aviva Surugeon